In the vast and distinguished world of American whiskey, no spirit is more celebrated-or more misunderstood-than bourbon. While many can identify its signature notes of caramel and oak, few can articulate with certainty what truly separates it from rye, Tennessee whiskey, or any other amber spirit. This is because the official bourbon definition is not a matter of opinion or regional tradition; it is a meticulous legal framework, a set of federally protected laws that guard the provenance and integrity of America’s Native Spirit.

This connoisseur’s guide will demystify that code. We will move beyond the myths and conflicting information to explore each strict requirement, from the 51% corn mash bill to the profound impact of aging in new, charred oak barrels. By the end, you will not only possess the clarity to identify a true bourbon with confidence but also hold a deeper appreciation for the heritage and craftsmanship sealed within every bottle. You will understand precisely how the rules create the spirit you admire.

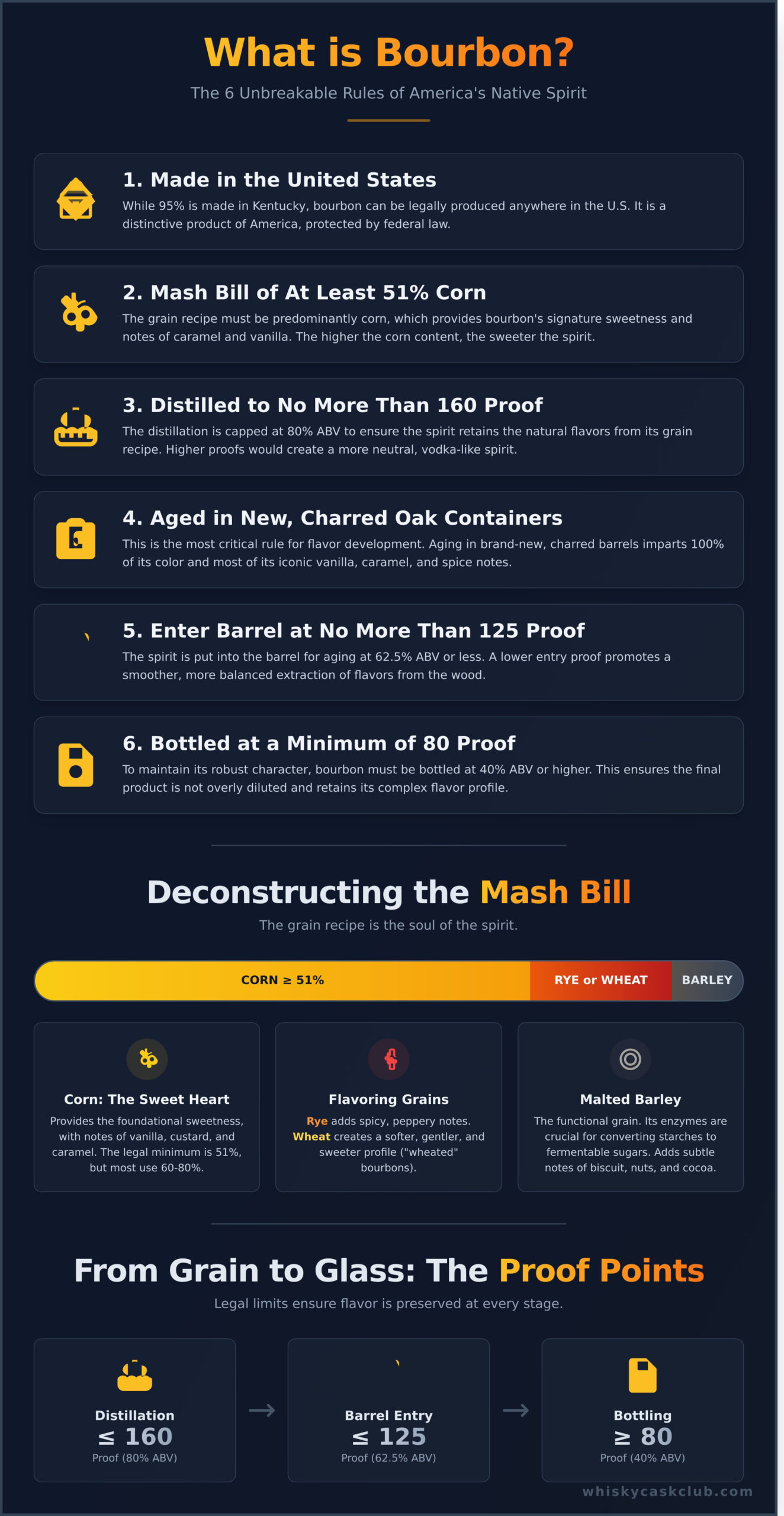

What is Bourbon? The 6 Unbreakable Rules

While many spirits are defined by geography, bourbon is defined by a strict set of laws. The official bourbon definition is not a matter of opinion but a legal standard, a testament to its unique American heritage. To be called bourbon, a whiskey must adhere to six foundational rules:

- It must be made in the United States.

- Its mash bill must be at least 51% corn.

- It must be distilled to no more than 160 proof (80% ABV).

- It must be aged in new, charred oak containers.

- It must enter the barrel for aging at no more than 125 proof (62.5% ABV).

- It must be bottled at a minimum of 80 proof (40% ABV).

In 1964, the U.S. Congress declared bourbon “America’s Native Spirit,” a move that enshrined its identity and protected its provenance on a global scale. This federal protection forms the bedrock of the official What is Bourbon Whiskey? standards. These regulations are not limitations; they are the very source of bourbon’s celebrated character, ensuring a legacy of quality and craftsmanship in every bottle.

1. Made in the United States

Bourbon is a distinctive product of the United States. While its historical roots are planted firmly in the American South-and approximately 95% of all bourbon is still crafted in Kentucky-it is a common misconception that it must be made there. Legally, bourbon can be produced anywhere in the U.S., from New York to Texas, as long as it follows the other five rules.

2. Mash Bill of At Least 51% Corn

The ‘mash bill’ is the grain recipe that forms the spirit’s foundation. The mandate for at least 51% corn is what gives bourbon its signature sweetness and full-bodied profile. The remaining grains, known as ‘flavoring grains,’ typically include rye for a spicy character or wheat for a softer, gentler palate, adding layers of complexity to the final product.

3. Distilled to No More Than 160 Proof (80% ABV)

Distillation is the process of separating and concentrating alcohol from the fermented grain mash. By limiting the distillation proof to 160, the law ensures that the spirit retains the distinct flavors and aromas of its core ingredients. Spirits distilled to higher proofs become more neutral, stripping away the very character that defines this unique American whiskey.

4. Aged in New, Charred Oak Containers

Perhaps the most critical and costly requirement, this rule dictates that bourbon must mature in brand-new oak barrels that have been charred on the inside. This process is non-negotiable and is where 100% of bourbon’s rich amber color and a significant portion of its flavor-notes of vanilla, caramel, and spice-are derived. The barrel can only be used once for bourbon.

5. Entered into the Barrel at No More Than 125 Proof (62.5% ABV)

The ‘barrel entry proof’ is the alcohol level of the spirit when it begins the aging process. A lower proof of 125 or less allows for a more effective interaction between the whiskey and the wood. This ensures a smoother extraction of desirable flavor compounds without drawing out the harsher, more aggressive tannins from the oak.

6. Bottled at a Minimum of 80 Proof (40% ABV)

To preserve the integrity and robust flavor profile developed during distillation and aging, bourbon cannot be over-diluted before bottling. This final rule guarantees a certain level of concentration and character in the finished product. While 80 proof is the legal minimum, many connoisseurs prefer premium expressions bottled at higher proofs for a richer experience.

The Mash Bill: Deconstructing Bourbon’s Flavor Foundation

If the barrel is where bourbon acquires its color and much of its mature character, the mash bill is where its soul is born. This grain recipe is the distiller’s first and most fundamental artistic choice, a meticulously crafted blueprint that dictates the spirit’s core flavor profile. While the legal framework of the bourbon definition is strict, it provides a canvas for immense creativity. The law, as outlined in the Federal Standards of Identity for Bourbon, mandates a mash bill of at least 51% corn. However, most distilleries use a significantly higher percentage, often 60-80%, to establish bourbon’s signature character.

The Role of Corn: The Sweet Heart of Bourbon

Corn is the non-negotiable heart of bourbon, providing the foundational sweetness that defines the category. Its high sugar content imparts classic notes of rich caramel, vanilla, and crème brûlée, creating a full-bodied and often viscous mouthfeel. This reliance on corn is a direct link to American heritage; it was a plentiful and robust crop for early distillers, making it the logical and economical choice for a uniquely American spirit.

Flavoring Grains: The Spicy Rye vs. The Soft Wheat

The remaining portion of the mash bill is where a distiller truly distinguishes their spirit. The choice of “flavoring grain” creates two primary styles:

- High-Rye Bourbon: By using a significant amount of rye (often 20-35%), distillers create a bourbon with a bold, spicy, and peppery character. These expressions often feature notes of baking spice, mint, and black pepper, offering a robust and complex finish.

- Wheated Bourbon: Substituting wheat for rye results in a dramatically different profile. Wheated bourbons are softer, gentler, and sweeter on the palate. They are prized for their smooth texture and notes of honey, baked bread, and toffee. The iconic Maker’s Mark is a quintessential example of this elegant style.

The Forgotten Grain: Malted Barley

While corn provides the sweetness and rye or wheat adds distinct character, malted barley plays a crucial, often overlooked, role. Its primary function is not flavor but science. Barley contains essential enzymes that break down the grains’ starches into the fermentable sugars that yeast consumes to create alcohol. While its role is functional, it also contributes subtle, complementary flavors of toasted nuts, biscuit, and cocoa, adding another layer of complexity to the finished spirit.

The New Charred Oak Barrel: Where Spirit Becomes Bourbon

While the grain recipe provides the spirit’s soul, the barrel is undoubtedly its heart. It is during the years of silent maturation inside a new charred oak container that a harsh, clear distillate is transformed into the complex, amber-hued whiskey we know as bourbon. This step is not merely influential; it is the single most important factor in determining the final flavor, aroma, and color of the spirit. The legal insistence on using a new barrel for every batch is a cornerstone of the bourbon definition, a rule with profound implications for quality and the industry at large.

This single-use mandate has cultivated a thriving American cooperage industry, dedicated to the craftsmanship of barrel-making. It also creates a valuable secondary market, as these once-used, flavor-rich barrels are highly sought after by distillers of other spirits, most notably Scotch whisky, who leverage the seasoned oak to mature their own expressions.

Why ‘New’ Oak is a Non-Negotiable Rule

The requirement for new oak is rooted in the pursuit of maximum flavor. A virgin barrel possesses its full, untapped potential of wood compounds like vanillin, tannins, and lactones. Reusing a barrel would yield a dramatically weaker, less complex spirit, as the initial aging process extracts the most potent and desirable of these elements. This strict standard ensures a consistent and robust character across the bourbon category, safeguarding its premium reputation.

The Science of the Char: How Fire Creates Flavor

Before it can hold any spirit, a bourbon barrel’s interior is subjected to an artful application of fire. This charring process does two critical things: it creates a layer of charcoal that filters out impurities like sulfur from the distillate, and it caramelizes the natural wood sugars just beneath the surface, forming what is known as the “red layer.” Coopers can control the intensity of this process, resulting in different char levels:

- Level #1: A light toasting, completed in about 15 seconds.

- Level #2: A heavier toast, taking around 30 seconds.

- Level #3: A 45-second char, the most common level for major distilleries.

- Level #4: A 55-second burn that creates a deep, scaly “alligator” char, imparting intense notes of smoke and spice.

How the Barrel Imparts Color, Aroma, and Taste

As seasons change, temperature fluctuations cause the bourbon to expand and contract, forcing it deep into the wood’s pores and pulling out flavor. This interaction extracts vanillins (vanilla), oak lactones (caramel, coconut), and tannins (structure and spice). Over time, slow oxidation through the porous oak further develops the spirit’s complexity. Crucially, every drop of bourbon’s rich, amber color comes directly from this process. The strict standards of identity, as outlined in the U.S. Federal Definition of Bourbon, prohibit any color additives, making the barrel the exclusive source of its authentic, natural hue.

Proof & Purity: Understanding the Numbers

The legal framework for bourbon is precise, particularly concerning its alcoholic strength at each stage of production. These regulations are not arbitrary; they are the architectural pillars of quality, meticulously designed to manage and preserve flavor. Simply put, ‘proof’ is a measure of alcohol content, precisely twice the Alcohol by Volume (ABV). These three critical numbers-160, 125, and 80-are fundamental to the bourbon definition, acting as essential guardrails that steer the spirit away from neutrality and toward profound character and heritage.

Distillation Proof (Max 160): Preserving the Essence

Distilling to a lower proof is a deliberate act of preservation. By capping distillation at 160 proof (80% ABV), the law ensures that essential flavor congeners from the corn-rich mash bill are carried into the new-make spirit. It is the difference between crafting a rich, complex stock and a thin, watery broth. In sharp contrast, spirits like vodka are distilled to 190 proof or higher, a process that strips away the character of the base grain to achieve neutrality. Bourbon, by its very nature, celebrates its provenance.

Barrel Entry Proof (Max 125): The Perfect Infusion

The interaction between spirit and wood is where the magic of maturation occurs. The maximum barrel entry proof of 125 (62.5% ABV) is a carefully calibrated ‘sweet spot’ for balanced flavor extraction. The chemistry is fascinating: water is more effective at extracting sugars and color from the charred oak, while alcohol excels at drawing out tannins and vanillins. This limit prevents an overly aggressive, woody spirit, ensuring a harmonious profile. This rule, established in 1962, is a key reason modern bourbons often present differently than their mid-century predecessors.

Bottling Proof (Min 80): Sealing the Quality

Before reaching the bottle, most bourbon is proofed down with pure, demineralized water to a more palatable strength. The legal minimum of 80 proof (40% ABV) serves as crucial consumer protection, guaranteeing a spirit of substance and preventing over-dilution. For the discerning connoisseur, expressions labeled Cask Strength or Barrel Proof represent the pinnacle of purity. Bottled at the proof they exited the barrel, they offer an unadulterated and powerful testament to the distiller’s craft-a core tenet of any authentic bourbon definition.

Beyond the Definition: Classifications That Signify Quality

While the six foundational rules establish the legal bourbon definition, the journey into a spirit’s true provenance has only just begun for the discerning connoisseur and astute investor. Beyond this baseline, several legally binding classifications signal a higher tier of quality and craftsmanship. These are not marketing terms; they are designations protected by federal law, each one a seal of quality that denotes superior care, transparency, and heritage. Understanding them is essential to navigating the world of premium American whiskey.

Straight Bourbon Whiskey

This is perhaps the most crucial quality designation beyond the basic bourbon definition. To be labeled “Straight Bourbon,” the whiskey must be aged for a minimum of two years in new, charred oak barrels. Crucially, nothing can be added to Straight Bourbon except for water to adjust the proof. This means no added coloring, flavoring, or other spirits. It is a guarantee of purity. If the spirit is aged for less than four years, its age must be explicitly stated on the label, offering another layer of transparency for the consumer.

Bottled-in-Bond: The 1897 Seal of Quality

A true mark of American whiskey heritage, the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 was a pioneering piece of consumer protection legislation. It was created to combat the widespread adulteration of spirits in the 19th century. To earn this prestigious designation, a bourbon must adhere to a strict set of rules, creating a government-backed guarantee of authenticity and quality. The requirements include:

- The product of a single distillery from one distilling season (either January-June or July-December).

- Aged for a minimum of four years in a federally bonded warehouse.

- Bottled at precisely 100 proof (50% ABV).

A Bottled-in-Bond bourbon is a testament to traditional craftsmanship and verifiable provenance.

Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey

While bourbon can be made anywhere in the United States, its heartland is undeniably Kentucky. To be labeled “Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey,” the spirit must be distilled and aged for at least one year within the Commonwealth of Kentucky. This designation is more than just a location; it speaks to a unique terroir. The state’s limestone-filtered water, which is naturally iron-free, and its dramatic temperature swings create an ideal environment for aging, imparting a distinct and sought-after character to the finished spirit.

Understanding these classifications empowers you to look beyond the shelf and appreciate the deeper story of craftsmanship in every bottle. For those dedicated to building a legacy through fine spirits, this knowledge is paramount. Discover how expertise in provenance can enhance your collection at whiskycaskclub.com.

Beyond the Definition: Your Legacy in a Cask

The intricate laws governing America’s native spirit are more than mere regulations; they are a testament to a rich heritage of craftsmanship. From the foundational role of the mash bill to the transformative power of a new charred oak barrel, each rule ensures a standard of quality and character. Understanding the official bourbon definition is the first step for any true connoisseur, unlocking a deeper appreciation for the spirit in your glass.

This same dedication to provenance and maturation defines the world’s most sought-after spirits. As global leaders in whisky portfolio management, Whisky Cask Club provides unparalleled expertise in tangible spirit assets. We offer our exclusive members access to rare and premium casks, turning a passion for fine spirits into a meaningful, alternative investment and a lasting legacy.

Your journey from enthusiast to investor begins here. Discover the principles of spirit maturation and investment. Take the next step in building your personal collection and securing your heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between bourbon and whiskey?

Think of “whiskey” as the broad category and “bourbon” as a distinguished member with a specific heritage. While all bourbon is technically whiskey, it must adhere to a strict set of U.S. federal regulations to earn its name. These rules govern everything from its grain recipe to the type of barrel used for aging. Other whiskies, like Scotch or Irish whiskey, follow their own unique production standards, resulting in distinct flavour profiles and legacies.

Does bourbon have to be made in Kentucky to be authentic?

While Kentucky is the undeniable heartland of bourbon production, accounting for the vast majority of the world’s supply, it is not a legal requirement. The official regulations state only that bourbon must be produced in the United States. This distinction is crucial to its identity as “America’s Native Spirit.” Bourbons crafted in states from New York to Texas are equally authentic, provided they meet all other federal standards for production and aging.

How long does bourbon need to be aged?

The law requires bourbon to be aged in new, charred oak containers, but surprisingly, it specifies no minimum duration. However, to be designated “Straight Bourbon,” a spirit must mature for at least two years. Any straight bourbon aged less than four years must state its age on the label. This maturation process is where the spirit develops its signature colour and a significant portion of its complex flavour profile, a testament to the craftsmanship involved.

What does ‘sour mash’ mean on a bourbon label?

The term ‘sour mash’ refers not to the flavour, but to a time-honoured production technique that ensures consistency between batches. In this process, distillers use a portion of a previously fermented mash (known as ‘backset’) to start a new fermentation. This method, akin to using a sourdough starter, helps control the pH level and promotes a consistent environment for the yeast, safeguarding the quality and signature profile of the final spirit.

Can you call a spirit bourbon if it’s made outside the United States?

Unequivocally, no. A core pillar of the legal bourbon definition is that it must be a product of the United States. This was officially declared by the U.S. Congress in 1964, designating it as a “distinctive product of the United States.” Any whiskey produced outside of American borders, even if it follows every other production step, cannot legally be called bourbon. This law protects the spirit’s unique American heritage and provenance.

Why can bourbon barrels only be used once?

The requirement to use new, charred oak containers is a fundamental tenet of crafting authentic bourbon. A fresh barrel imparts the maximum amount of flavour, colour, and character-notes of vanilla, caramel, and spice-from the wood. Using a barrel a second time would yield a vastly different, much milder spirit. These once-used barrels, however, begin a new legacy, as they are highly sought after by producers of Scotch, rum, and tequila for aging their own spirits.

What is the difference between bourbon and Tennessee whiskey?

The distinction is a matter of refined craftsmanship and regional heritage. Legally, Tennessee whiskey meets all the criteria to be called bourbon. However, it undergoes an additional, crucial step before barreling known as the Lincoln County Process. This involves filtering the new-make spirit through sugar maple charcoal, a process that mellows the liquid and imparts a signature smoothness. This extra step is what legally and stylistically separates it from its bourbon counterparts.